On Complexity and Monoliths

Putting microservices (and other architectures) in a realistic light without resurrecting what should stay dead.

Horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, in his short story The Nameless City, famously attributed this quote to a mad (fictional) poet:

That is not dead which can eternal lie / And with strange aeons even death may die.

And—yes indeed—here and now I will let the above refer to monoliths (and other phenomena) and not fictive gods sleeping in the ocean, waiting to consume humanity.

This article is reflective and highly opinionated in nature. If you want a more technical, objective approach to concrete solutions and discussions on this matter, then see for example these great books:

- Fundamentals of Software Architecture: An Engineering Approach

- Software Architecture: The Hard Parts: Modern Trade-Off Analyses for Distributed Architectures

- Building Microservices: Designing Fine-Grained Systems

Definition: Oh, and microservices don’t have to equate Kubernetes. For me, at least, that’s an entirely different point. I’ll instead think of function-as-a-service (FaaS) as a purer realization of microservices, even though the term “microservices” should be kept as generalized as possible in this article.

Final trigger warning: I won’t argue about monoliths for cases where they are rationally relevant, such as very limited/small scopes, prototypes, possible security reasons, and such. While monoliths can definitely be a valid architecture style, the proper analysis of the problem the software should solve, quality attributes, and understanding of the domain in which the software interacts cannot be skipped.

Reality check:

There is nothing inevitable about progress.

A lot of bad ideas have a tendency to come back after they’ve been hidden away long enough.

One of these ideas is the monolith. As with all ideas, even they make sense through a certain lens. And do hear me out! There are completely rational, valid, good reasons to use them sometimes—however, my reflection here is about what I take to be the root of the problem:

The problem represented by “monoliths” extends much further than just the technical side (i.e. a single deployable unit)—stretching from a lack of logical problem decomposition leading to collateral damage such as poor framing/scoping and communication issues.

How on earth did we get here?

Syntactic Prisons and Golden Hammers

Imagine a person just fresh out of school, or some program, or self-trained, who is now ready to start working with software “professionally”, whatever that entails today. They know all the syntax of one or more languages. But can they design? Most probably not. Syntax is not enough to make software.

If I can stick all the code in a box, won’t that be the right choice every time?

Building architects may complain that seeing an architectural drawing through—from start to finished building—is something that happens very infrequently for most, thus resulting in a slow feedback chain and slower “mastery” of the trade. Actually cutting the ribbon on a house is a luxury not afforded to all, and not very often.

And I don’t even actually believe all that much in software architects (as a role)—they aren’t even part of many “big tech” organizations—but I am a firm believer in software architecture and software design.

Yet the art of software design is lost, even in an age when it’s incredibly fast to build and make things out of code.

Software is not limited by physics, like buildings are. It is limited by imagination, by design, by organization. In short, it is limited by properties of people, not by properties of the world. “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

— Martin Fowler, “Who Needs an Architect?”

Software is the result of socio-technical processes. Programming alone does not make software. You may already think of (Melvin) Conway’s Law here, and how

“any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”

It would be easy to draw some kind of parallel line here to microservices. What if the tech was not the problem? It seems to me an entirely reasonable assumption that many of the organizations and people having strong opinions against microservices never had the conditions of success on their side. I believe I am right in that such organizations often exhibit tendencies of Taylorist management, “line/functional organization” and building sub-standard products because of a lack of customer dialogue, and the presence of vanity metrics and HIPPO-driven decision-making. Sounds rough and unfair? Sounds like most companies I’ve worked for and know of.

With pain, discomfort, and failure we as humans tend to clam up, freeze, resign to the elements, and otherwise harden the behaviors that lead us here. It’s like we gave up the same systems of belief and knowledge that we otherwise make use of! Frenzied cries are heard: “Microservices caused this and I want my golden hammer back!”

Given that “we can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them”—which we can probably, maybe, attribute to Albert Einstein—isn’t it then actually a completely rational response to the complexity of microservices, cloud-native, and all of that hoopla, to return to something “simple” that “worked”? So let’s think about why monoliths might be an attractive idea (or well-worn sofa) these days.

No, A Monolith Is Still Not The Solution

Kamil Grzybek’s article on modular monoliths is excellent. What I want to contest is that you don’t need a monolith to do that — the monolith just adds pain to the otherwise good general concepts of structure and decomposition. You can actually build in the traits of such an architecture into a function-as-a-service (FaaS) setup too. The big thing we have in common — and his DDD project is a good example — is that with well-considered software architecture (i.e. modules…) we can decompose the system into good, logical segments. That’s a good thing.

Ergo: If you are hating on microservices you are missing the point.

Microservices don’t have to mean that each Lambda (or whatever FaaS you are thinking of) is totally self-sustained, free-floating in the Platonic universe, without complex modular/class-oriented interactions — my own Get-a-Room DDD project and my online DDD book shows as much. And they aren’t deployed willy-nilly into space like satellites — they are part of some context, typically a service, with its own interfaces.

Welcome to the fast track, taking you from a DDD novice to actually understanding a real, modern application built with…ddd.mikaelvesavuori.se

Doing it in a sane, neat way (as per the links), you get independent deployability, a smaller surface of errors, and a more exact infrastructural depiction of your system — without resorting to a monolithic deployment: The thing that Kamil rightfully says is the only true property of a “monolithic” system.

Even in that monolithic model, you’ll perhaps use async communication with service/event buses and whatnot to pass on commands and queries to other modules. This is the point where I find the irony creep up: How is this not more logical and natural in a FaaS landscape?

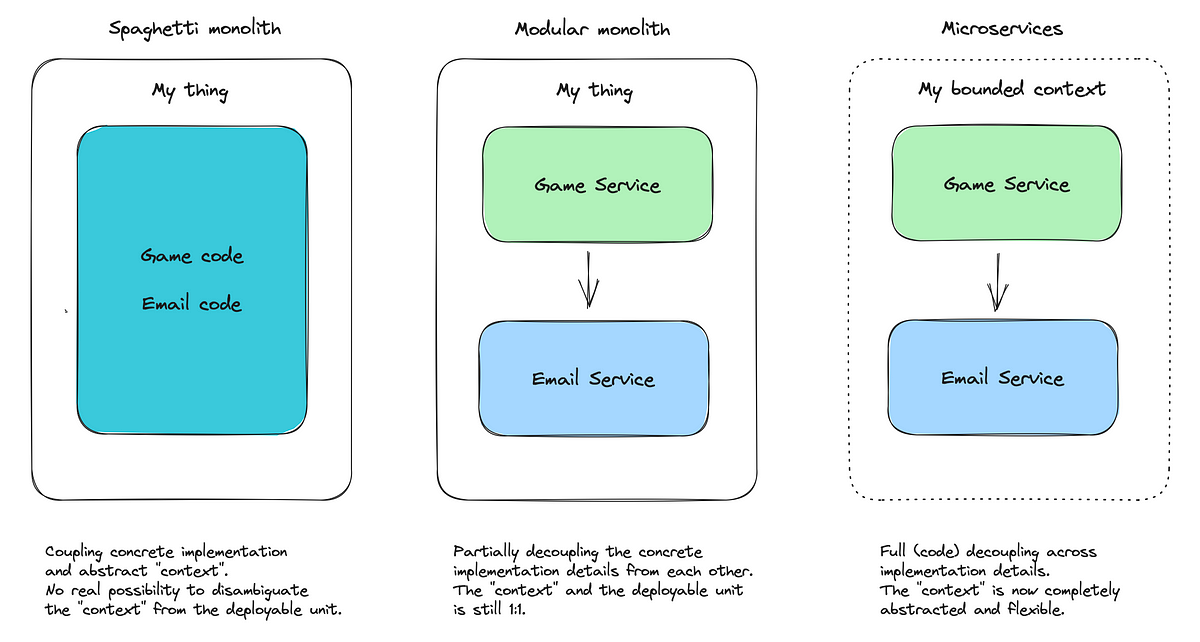

The modular monolith is still just a single deployable unit but with good, clear separation in its code. Nothing bad about that on its own, but we are now racing into a mix-up of the infrastructural side with the actual application code — not good!

Let me be clear and call something out that’s a bit painful: As insinuated before, the same people who fail with microservices, also seem to be those who fail with their “modern” architecture, their communication, their separation of concerns… Because, after all, what are microservices other than a merely infrastructural representation of those (more abstract) concepts? How on earth is a modular monolith (or any monolith for that matter) going to be easier to work with or understand, than something that is clearly outlined and independent and semantically differentiated?

Microservices, together with a dab of plain logical decomposition and Domain Driven Design, can make your solution a lot more expressive without that much additional overhead. It’s not that hard!

In other words, I wonder:

How can a big, undefined f***ing thing be a better architecture than a small, well-defined f***ing thing?

I wonder. I really do.

The much more moderate approach here is of course to remind ourselves of the 8 fallacies of distributed computing and all of the ways in which network communications can fail: By adding more dependence on the network we make it (on the whole) slower and more brittle. This is true to some extent, but every architecture is also “the least worst one”, so even an extremist should be able to choose whether the separation of concerns and independent infrastructure and deployability is more (or less) important than not having them, instead addressing some other, more desirable architectural properties.

High Complexity—The Slow Death

As a youngster, I was misled to believe that the primary type of software complexity is mathematical, or something similar and scary, which I hated. Much, much later I found out that it’s not true — the complexity is of a linguistic and processual nature. Given that the majority of software is enterprise/business software, the big thing to deal with is a concrete and truthful translation of processes into code.

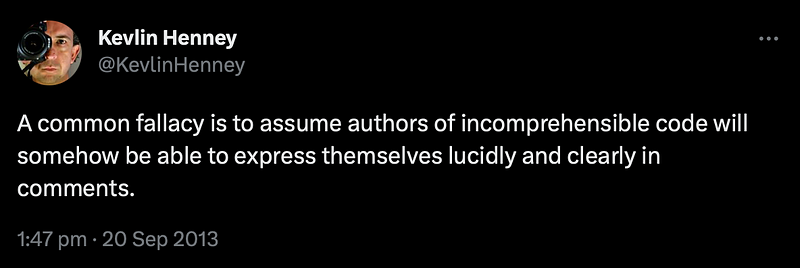

So, if one’s misguided belief is that “complex code” is a given because of “algorithms” and “mystery black boxes”, then I’ll happily pop that bubble: Good code should (at least) be understandable in syntax and structure (system design as well as application architecture), and include an appropriate degree of crisp documentation to explain and visualize processes that are not immediately visible in the code itself. Good code is dumb, boring, and predictable.

Without derailing too deeply into “bad versus good” code, some of the many measures of understanding complexity in software — such as cyclomatic complexity and coupling — are tremendously useful. Safe to say, in my tech career I’ve had a lot more use of my BA in English (and the humanities subjects I took) than of any of the actual technical studies I’ve taken, as such a background makes the semantic and organizing challenges much, much easier.

Spaghetti code is the devil’s doing, and it tells a story not just of bad programming, but a disregard (or misunderstanding) of what is actually being modeled. I’m sure there are some jobs out there for algorithm math wiz kids and data scientists, who use “programming” in the broad sense of the word, but not in a process-oriented or socio-technical context. For the rest of us, building such systems, spaghetti code is the thing you must fear the most.

Words mean things and if you don’t understand that, then you should reconsider the profession. That the classic book Clean Code has to go to great lengths to clarify this is painful to me.

And the most important words are the requirements (or your similar concept).

Modern organizations have no problem asking people to build something that is not even understood, and for software engineers to say they are unable to test something because they don’t know how it should work (even if they built it themselves!). This isn’t complexity, it’s stupidity. There is not a sensitive, nice word for this.

Because this fact around actually experienced complexity/stupidity, brought on by not (for example) having complete or logical requirements is not well-understood, many organizations believe that developers will be able to solve (business) complexity based on any set of information, good or bad. Alas, this is not the case.

Enterprise software can never be better than the thing being modeled and the level at which it is expressed. Cognition, competence, attention, and all kinds of other factors will depreciate that original value as soon as the process and requirements come into contact with reality. Better be prepared!

I recently saw the above behavior called out as “logical debt”, which I think is a brilliant encapsulation of what we are talking about.

In theory, it seems we are happy to talk about essential complexity—the nature of the problem itself—but in reality, it seems like it just doesn’t unfold that way. However, instead, what follows as a second-order effect is complication or perhaps even outright accidental complexity — brought on by our ways of solving it (ending in more issues being created). So, rather than being pure and attacking the root of the problem (because we are unable to fully define it) we’ll let artificial urgency and other things take control, leading to logical debt as well as technical debt.

You might be interested in my article on technical debt:

A really important question is therefore: Are we, too, over-complicating things? Complication, as opposed to complexity, is a class of problems that has known, predictable solutions. Aren’t microservices more complicated? Indeed, in certain aspects. Not necessarily, however, if you use FaaS or similar constructs. But you also gain things, of course.

Perhaps the most important boon of microservices is that they make embracing Gall’s Law easier:

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over with a working simple system.

Small, “dumb” things work. Certainly when they have clear responsibilties. I am, as you’ve read, arguing that a more explicit and semantic, disambiguated way of making and deploying software is the better way. Microservices allow you to do so.

Because of the coarse-grained barriers of a monolithic codebase, monoliths are logically more susceptible to accidental complexity. Let’s also be real and understand that complexity is not just “a minor friction”—it could spell the end of your work, career, and others’ lives. There’s just such a litany of projects that fail due to complexity (including accidental complexity due to poor planning, communication, etc.) that it’s hard to even pick examples, but maybe let’s call out these for the hell of it:

- Windows Vista

- Boeing’s 737 Max disaster

- Tesla’s self-driving feature

- The UK’s National Health Service

- NASA’s Challenger space shuttle disaster

- Knight Capital Group’s “glitch” that cost $400M+

- The Swedish Öppna skolplattformen (“open school platform”)

- Any number of SAP implementations (if my sources are correct)

Actually, the majority of software projects fail, if anecdotes and various internet reports are true, which seems plausible enough for me.

For more on complexity, see Fred Brooks’ classic paper “No Silver Bullet: Essence and Accident in Software Engineering” (1986) and the Cynefin Framework.

Complexity is not abstract, it is tangible. Ask anyone writing the code.

As far as I care, engineering is about reducing unknowns and complexity. It’s not engineering if that’s not what happens as a result. And hiding the details of a system in an undefined black box sure sounds like a poor idea to me.

The monolith thus encapsulates a rapid, rabid regression; desiring simplicity but fundamentally unable to cope with handling the on-set of complexity. Sure, you get fewer seams in a monolith — but the seams are there to segregate, name, and identify different needs. Naming is one of the two “hard things” in computer science, and this is still easy compared to software design: You’ll need to name, separate, and differentiate a lot when migrating from a spaghetti bowl to microservices. Yep, it might be easier to deploy a monolith in some sense, but every change also may impact everything else. Not good.

It is also much too trivializing and anti-intellectual to draw lines like ”you are not Netflix” or ”you don’t have a complex system”. But the thing is: Practically everything is distributed in computing — you already have a distributed system!

Monoliths have technical properties that are different from microservices but the pains of microservices get outed because of unsolved complexity and unclear mental models. The attacks on microservices might as well be seen as Freudian slips from the aggressors, explaining what they did not have in place, themselves.

People and the organization of them (i.e. teams) is a central aspect of the DevOps model. Logically there is nothing to say all microservices could not be owned and run by a single team. The contention comes with ”sharing” stuff. I ask myself: Why is it a problem to create systems with boundaries? To ask people to be responsible for different parts?

Same thing for those complaining that microservices are bad or hard because you might need (?) to co-deploy changes — you have completely missed the crucial work of isolating your service! That’s not a microservices problem, it’s a “you” problem!

So, maybe you are considering changing your mind? Hard fact: Unless you have an organization that can adopt to specific, mostly non-overlapping products/features/concepts, then no, microservices won’t be exactly easy to work with. But they might still be better (as a stepping stone) than a ball of mud monolith, as you get the previously stated benefits that I thoroughly believe in. It might just be worth it.

The Loss of Language and All That It Entails

We are overthinking software and underthinking everything else around it.

Code is there to solve problems. If we are unable to enunciate the problem and our desired state, then we should not (can not, even) propose and create a solution to it.

I’d wager most mismanagement and issues with process (etc.) come from going to a solution without that clarity of the problem and respect towards things changing over time.

If, God forbid, the code actually becomes the problem then we are in deep shit, left with twice as many problems. And this will happen as a matter of logical course since the code does “something” but it’s yet to be defined (note: not in the positive “agile” sense).

And ”business” will never complain about the first ”unknown/unknowable” problem (which is intangible), only the new one you just created trying to be a “Good Boy” and do your job.

Zoom to the big picture.

I believe the failure of our society in terms of teaching critical and rational thinking is part of this challenge and state of affairs. Our education system is also failing the training of BAs, engineers, and other IT roles. Look no further than Jim Aho’s article on this.

When I say Business Analyst (BA), I mean a person whose primary purpose in the company is to translate business needs…blog.steadycoding.com

I am immensely scared of our basic education going under. Loss of critical thinking, loss of contextual action and initiative, and loss of language (bad grammar = bad code is 100% a real problem) will not improve the statistical possibility of building high-functioning organizations, ”things”, and solutions to real-life problems.

And Big Tech agrees that these skills are important, as mentioned by Irina Stanescu on LinkedIn:

In my 14yrs career in engineering working for Big Tech companies such as Google and Uber, there is no other skill I used more than writing. And no, I don’t mean writing code. I mean English writing. Emails, Design Docs, Presentations, Feedback, Code Reviews, you name it.

Like Dante descending further down into Hell, we’ll see more evidence of this corruption and the impact on software engineering. Multi-year ideas that do not transfer anywhere from concept to realization but only into Powerpoint bullets and urgency-doped “task forces” that are put into existence and then dissolved with nary a shrug are key examples of this state of affairs. The acceptance of illiterates who can just barely do their jobs to lead organizations is such a depressing state that even quantifying it in money is not enough.

Let me share two examples of my own, even if they aren’t quite that extreme.

The “simple” mega task

I remember talking to a colleague many years ago—he was on the project/product side—trying to make him understand Kanban. After some time and thinking he said:

“Can’t we just make it one task: ‘Finish the thing’?”.

🤷♂

The diagram with a literal black box to solve all problems

I once had to literally call out an ”architecture” as a “Donald Duck diagram” as it was supposed to depict a key feature but was hardly even a cartoon sketch. It wasn’t a proud moment for me but somewhere we have to draw the line between frankness and courteously head-nodding your way into a grave. Time was running out and this is what the great minds had concocted!?

Helping remediate this, we have since designed and operationalized that key area, but becoming less than a victory it became a reminder that bad things happen when the wrong people are ”enabled” to work autonomously. Would be nice hearing this other side of the coin from all the happy-go-lucky DX research being done.

Note: This is not an apology for ARBs or ITIL, but f**k me — some people really need to get themselves a different career.

Without a language and supporting skills/org/structure, there is no way to solve this complexity conundrum. I have yet to meet a professional who can express domains, models, boundaries, and technical interfaces who would also want to make a move back to a monolith (the Amazon Prime case being a good counter-example!) once they are running in microservices.

Also, I seldom see critiques that adequately—or at all—show any knowledge of the professional know-how outlined in the key literature of our profession. It’s simply impossible to say what people did to prepare themselves for microservices, but I just can’t imagine all these failures if they had done their prep work (as mentioned several times by now).

Being able to work with microservices and modern distributed architectures is, as always, based on your application of skills that have always been part of what a software engineer should do. That width and ”literacy” we are lacking now when 10–15 years of ultra-niche job specs and 6-week ”get an IT job” programs have ravaged the industry, with people of an equally low expected caliber and organizations that seem traumatized by how bad it can go.

I mean: You will see the big tech companies placing a big portion of their attention on your social as well as literary skills in the form of code reviews, system design work, and argumentation around solutions. Are you not? Building distributed systems is not an “off-beat” experience in 2023. None of these things are impossible to learn, but you will learn most of them away from the keyboard. The introverted keyboard warrior was not what the software engineer was expected to become.

Somewhere someone has to step forward: Why the hell did our organizations and hiring managers accept this? Losing literacy and these important, general human qualities to dead-stupid syntax-crunching is messing up our chances of a viable, professionalized trade. Robert C. Martin even wrote about software engineering not deserving to be called a “profession” in the strict sense of the word. Because, after all, what is it that we profess? I think it’s a fair question, when we can hardly, at the grand scale of things, do the “engineering” part competently in light of how we interact with our stakeholders.

Endnote: A Simpler Future

Complexity and the self-help industry are somewhat similar. Ironically self-help books or thinly veiled programs (even something innocuous like Bullet Journaling), will express some core value or virtue as being desired, and that this specific guide will “unlock” how you can programmatically attain this desired thing — time, money, energy, sleep, fitness, whatever.

In the somewhat flock-like and banal human behaviors we exhibit, we’ll calendarize and structure this necessary work effort to follow our new life philosophy or vague spur-of-the-moment. And the majority of self-help really never works. I believe the real point is that in many cases, self-help authors are earnest in providing their program — it worked for them! Perhaps even for some others. But the thing is that psychology is a really complex (in the real, actual sense) area. If it works or not for you will also be mostly down to luck, persistence, and what fits your personality.

Most programs will say they are easy or some similar sentiment to make contextual sense. However, what they all do is add more. Do more of this, do more of that. I’ve always been a lot more reductionist and found Zen Buddhism interesting (though I’ve never been a follower).

What I try to live by is a rule of less: Remove choices. Stay with one haircut. Use essentially uniform clothing. Be freer as a consequence.

The reward I gain, personally, is saving energy and being able to expend it where it matters; my projects and (in terms of pure hours) much bigger ability to spend time doing things I want, which I know is not nearly a fact with most people in between work, kids, activities, and all of that.

Don’t let your passion to complex problems drown in the merely complicated and undefined.

The answer to reducing complexity is to move towards fewer moving parts, and more precise definitions of identity (what the “thing” does). Don’t build what you can use off the shelf. Don’t build what you don’t understand and can’t draw, talk about, or explain. While a monolith superficially has fewer moving parts, that’s because we hide them in a black box without insights.

Take a hint from the design literature—we should look to attain a wider vocabulary, thinking for example about affordances (Donald Norman) and about how limitations can actually make our work better. Clarify the problem, and simplify the solution to solve it. Tech is too eager for the hotness and newness and this hurts us more than it helps us—But microservices are not some new “hotness”, it’s an infrastructural representation of clear responsibilities. That’s timeless.

On a last note: A tombstone is also a monolith. 🪦 They tend to come with an obituary.